“3 out of 4 Americans believe that killing animals for meat is immoral, according to a MSNBC-MediaMatters-PETA poll. Based on this information, Congress is debating new rules put forth by the FDA to tax meat production at a higher rate than vegetables.”

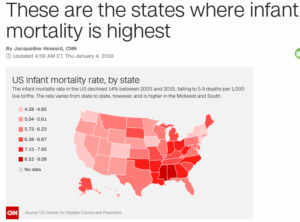

The infant mortality rate is nearly double in Mississippi and Alabama than it is in New York and California!!!! Oh wait, It is 0.4% in NY and CA and 0.8% in MS and AL. And wait, there’s more! There’s a longstanding and well-known correlation between poverty and higher infant mortality. CA and NY are 2 of the richest states and MS and AL are 2 of the poorest states. What, exactly, is the point of this article except to poor shame the south?

Every media outlet has published a metric ton of articles that start just like this. It’s lazy writing, but it’s also the platinum standard for crafting a narrative. See, people are social animals that are primed to go with the crowd. When that subconscious impulse is manipulated through polling, people’s behavior becomes malleable. When you have some basic understanding about the strata of voters and their belief systems, you can get them to do your bidding without them even knowing.

Three basic concepts make public opinion polling an irresistible tool used to bias an audience: herd behavior, identity politics, and aura of authority. The formula is simple, using a favorable polling result, generalize the findings so that it is implied that a majority of an identity group believe a certain way, relying on herd behavior to solidify support of the belief within the identity group.

The ironic part is that none of what makes public opinion polling such a strong tool is based in reality. The herd behavior is based on an illusion. By and large, support for a politically controversial position sits somewhere between 40% and 60%, meaning that nearly half of people oppose said controversial position. Further, polling doesn’t allow for enough nuance to differentiate between being opposed to legalizing machine guns and being for the repeal of the 2nd Amendment. Identity politics, as well, is subtle. Take, for example, the approval/disapproval ratings of prominent politicians. If identity politics were the primary driver of public opinion, the surges and drops in approval ratings would be quite attenuated.

However, the illusion of universal agreement is very powerful.

Social Science is Modern Day Astrology

The holy grail of science is replicability. If you can produce an effect in one study, you should be able to replicate the conditions and achieve the same effect in a successive study. In physics or chemistry, this is usually fairly straight forward. Barring some unknown environmental variable affecting the experiment, the bowling ball and the feather land on the ground at the same time in a vacuum. The sodium and the water create a highly exothermic reaction when combined.

Social science is much squishier, both in methodology and in result. When you’re working with people, they don’t behave like molecules in a vacuum. They lie, they are affected by minor biases in your methodology, they are subject to many weird psychological effects like the placebo effect, and they don’t take kindly to being locked in a laboratory for 15 years for a longitudinal study.

Social science is much squishier, both in methodology and in result. When you’re working with people, they don’t behave like molecules in a vacuum. They lie, they are affected by minor biases in your methodology, they are subject to many weird psychological effects like the placebo effect, and they don’t take kindly to being locked in a laboratory for 15 years for a longitudinal study.

Resultantly, more social science is done by “poll” than by “experiment.” Not that the experimental method is any better. I experienced the infamous psychological experiment where they flash pictures of different races of people and then time how fast you click on the good word or the bad word.

This has led many skeptics to put scare quotes around social “science”, which more and more resembles phrenology than physics. Adding more fuel to the fire is the “replicability crisis.” The replicability crisis affects both experimental and poll based studies. Essentially, social science can’t find the same effect two times in a row. Not only that, but they can make a study say that any effect exists (such as, listening to songs about old people makes you younger).

However, in a world that fucking loves science and decides social policy by sound byte, the internal crisis in social science becomes a very public issue. As discussed in Part 1, science journalism is a farce. When an ethically compromised journalism industry interacts with an ethically compromised social science industry, you get science journalism that is slave to the agenda of the media. We live in a world where science is subservient to the state. If you publish something that aligns with the state’s goals, you get media coverage and additional grant funding. If you try to publish something that goes against the state’s goals, you get undermined at every step.

Manipulating the Results: Bias in the Experiment

People are quite malleable as I’ve already said, and this is evident in the results of studies. Wording is very important. Want an anti-abortion poll result, mention “mother” and “convenience.” Want a pro-abortion poll result, mention “choice” and “woman”. I’ll let the next example speak for itself.

An example of a wording difference that had a significant impact on responses comes from a January 2003 Pew Research Center survey. When people were asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule,” 68% said they favored military action while 25% said they opposed military action. However, when asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule even if it meant that U.S. forces might suffer thousands of casualties,” responses were dramatically different; only 43% said they favored military action, while 48% said they opposed it. The introduction of U.S. casualties altered the context of the question and influenced whether people favored or opposed military action in Iraq.

There are quite a few known phenomena that influence studies, as well.

Acquiescence Bias – Making a statement and asking the poll taker to agree or disagree. Usually folks with lower education will agree disproportionately with the statement in comparison to when the same issue is asked in a question format.

Acquiescence Bias – Making a statement and asking the poll taker to agree or disagree. Usually folks with lower education will agree disproportionately with the statement in comparison to when the same issue is asked in a question format.

Social Desirability Bias – We saw a bunch of this last election cycle. People tend not to like to tell others about their illegal or unpopular opinions, so they’ll simply lie to make the poll giver like them.

Question Order Bias (“Priming the Pump”) – Ask a question that will likely get a positive or negative reaction, then follow it with a question you want to influence in that positive or negative way. For example, if I were to ask y’all whether you like the current spending levels of the federal government and then followed it up with a question of whether you like deep dish pizza, the pizza question will be skewed negative.

Interviewer Effect – Related to the Social Desirability Bias. The poll taker changes their responses based on characteristics of the poll giver. For example, if a woman is giving a poll on equal pay, the poll taker may respond more favorably than if a man gives the poll.

Observer Effect – The poll taker is subtly affected by the poll giver’s unconscious cues, resulting in their responses being biased toward the poll giver’s expectations. For example, if the poll giver expects that black people will answer a question a certain way, they may change their inflection when asking the question in a way that influences a black poll taker to answer in that way.

This still ignores the cognitive biases that we have talked about in Parts 1 and 2.

How do you sort through all this crap and get to a real, measurable effect? You design a good experiment. How do you design a good experiment when taking a survey? You don’t.

Manipulating the Results: Playing with the Data

Okay, so we have highly questionable data from a shit survey, but at least we’re now in the realm of math. Nothing can go wrong here!

I’m going to start with a book recommendation: How to Lie with Statistics

A core requirement of legitimate polling is “randomization.” Taking a random sample of the group you’re trying to study is what allows you to generalize the results to the group as a whole. If you do something to disrupt the random sample, you weaken the ability to generalize the results to the group as a whole.

How do people screw with the random sample?

Weighting – Let’s say you’ve done a 1,000 person survey, but you’re concerned that your relatively small (but random) sample isn’t actually representative of the world. See, you’re a savvy poll taker and you know that a recent poll showed that there are 41% Democrats, 37% Republicans, and 22% Independents in the locality of your poll, and your poll has 39% Democrats, 40% Republicans, and 21% Independents. We’ll just inflate the results of the Democrats in the poll to reflect 41%, deflate the result of Republicans to reflect 37% and mildly inflate the results of the Independents to 22%, and we’ll do our further analysis based on this massaged data. Of course, this assumes that the pollster’s understanding of reality is correct, and it screws with the randomization of the data, resulting in a strong danger that the data no longer reflects reality.

Margin of Error – You survey 1,000 people, and 44% love Trump and 46% hate him. Therefore, Trump is unpopular on the net. Well, except for the margin of error. For a 1,000 person survey in a country of ~300 million, the results are roughly correct. Roughly correct means that your poll (and others designed in the same way) is within 3% of the reality 95% of the time. This, of course, assumes a representative (read random) sample.

Data dredging – Let’s do a huge survey asking a zillion questions. Then let’s go fishing for correlation between variables. We’ll just ignore that correlation does not imply causation, because who actually believes in that. It actually makes for some amusing reading.

Fudging the data – How about we do 15 runs of the survey, pick the 3 that most support my hypothesis, and publish a paper with the results of those 3 data runs?

A more technical issue is highlighted in Anscombe’s quartet. Four completely different sets of data that are statistically identical. Why? Let me tell a story from Poli Sci 300-something, Statistics for Political Science. One of the main statistical analyses performed by Poli Sci statisticians is linear regression. Linear regression (which you may remember from 5th grade math) is trying to fit data to a straight line (technically you can fit it to another curve). However, the problem is that you have to predetermine the type of curve you’re fitting it to. It doesn’t self-tailor. If you have an exponential relationship between being libertarianism and small government views, it won’t fit well to the straight line regression. It struck me, sitting in that class, how much statistical analysis was an art, not a science. If you don’t understand the math and conceptual understanding behind the numbers (as most social science students don’t), you’re going to come to somewhat worthless results when doing statistical analysis.

The Results are Garbage In the First Place: The Telephone Problem

Garbage in, garbage out. It’s pretty much my motto. It’s especially true with public opinion polling. Let’s quickly mention two issues so you get a sense for the type of garbage being used in modern public opinion polls. No need to linger on this issue.

1) Self-selection bias – This has always been there. Who is likely to answer a telephone poll? Is there some inbuilt bias caused by some declining to participate? Is there a destruction of the randomness of the sample if it takes 3,000 phone calls to get 1,000 poll takers?

1) Self-selection bias – This has always been there. Who is likely to answer a telephone poll? Is there some inbuilt bias caused by some declining to participate? Is there a destruction of the randomness of the sample if it takes 3,000 phone calls to get 1,000 poll takers?

2) The shift away from landlines – This is new. Currently, less than 50% of people still have landlines. Cell phones really screw up some of the assumptions behind the methodology of telephone polling. For example, if a pollster wanted to survey people in central Indiana about some local issue, it’s possible that I would get a phone call. I don’t live in central Indiana, and haven’t for over 5 years. What does it mean for the poll that I’m not in the expected cohort? Nothing good. However, it’s easy enough to ask where I live at the beginning. What about the other way around. A pollster is trying to survey northern Virginians about some local issue. I’m essentially disenfranchised by that poll because my area codes is central Indiana. Further, cell phones make it really easy to block unknown numbers, resulting in even fewer “hits” for each phone call.

Knowing the Public: What Motivates Voting Behavior?

Now that I’ve thoroughly shattered your trust in the public opinion poll, let me shatter your trust in the people being polled. Let’s talk about a truly experimental social science study looking at beliefs and voting patterns.

The nature of belief systems in mass publics 1964 – Phillip Converse (His earlier work, The American Voter, is a good read, too)

The interesting result of this experimental study of people’s beliefs and voting habits is this:

There are 5 different types of voters:

- Ideological – Able to abstract their issue positions into larger conceptualizations (principles) and set those conceptualizations relative to other ideologies.

- Near Ideological – Have awareness of an ideological spectrum, but their positions don’t particularly rely on an ideology.

- Group Interest – Good ol’ identity politics. I’m black therefore I vote Democrat.

- Nature of the Times – Something bad happened in the world when Republicans were in power so I’m voting Democrat.

- No Issue Content – I vote because…well… argle bargle, incoherent rambling, no making sense. Seriously, this is the category where the pollster couldn’t make any sense of their motivations for their beliefs.

There must be a bunch of people in groups 1 and 2, a ton in 3, and a smaller amount in groups 4 and 5, right? That would be the sort of society I want to live in.

Sorry to disappoint.

Group 1 (Ideologues) – 2.5%

Group 2 (Near Ideologues) – 9%

Group 3 (Identititarians) – 42%

Group 4 (Idiots who can rationalize their opinons) – 24%

Group 5 (Idiots who can’t even coherently explain the reason for their opinions to a pollster) – 22.5%

This was taken in the early 1960s. Wanna bet it’s even worse today? Identity politics wins because that’s how a plurality of people think. Principals over principles is a thing because 42% of people care about principals and 11.5% (generously) care about principles.

The sickening part is that group 4 and 5 vote. (Table 1 of the study shows the percentages for the study as a whole and for likely voters, with only marginal changes to the percentages).

I could type more about the horrifying prospects of society based on this study, but I think it’s more impactful to let the data sink in. 89% of people base their worldview/politics/beliefs on something other than a set of principles/ethics/morals. Almost 50% have blatantly idiotic reasons for holding their opinions.

As a final note, 35% of respondents randomly varied across opposing positions for issues in successive interviews. There wasn’t a trend in these changes, which made the pollster come to the conclusion that these people weren’t able to come to the same opinion two interviews in a row.

Quick Takeaways from the series of articles

- The media is untrustworthy, and not just in the obviously biased ways

- Gell-Mann amnesia is real

- Science journalism is neither about science nor is it good journalism

- Any conclusion drawn from social science should be viewed with great skepticism

- Anything being pushed based on majoritarian or poll-tested bases is probably shit

- By thinking in terms of principles, you’ve elevated yourself into rarified air. Most people struggle to even rationalize their opinions.

“3 out of 4 Americans believe that killing animals for meat is immoral”

Who would even believe this?

3 out of 4 Americans are Morons, Sheeple and some I assume are Good people

To be clear I made that part up.

After reading what you wrote, I can see a Poll designed to get just that conclusion, So Just because it’s Fake News doesn’t make it Untrue

Truthy.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/dec/11/meat-tax-inevitable-to-beat-climate-and-health-crises-says-report

I support your vegetable tax.

Nathan J Robinson?

https://www.currentaffairs.org/2018/01/meat-and-the-h-word

NJRis one of the best at making incredibly stupid, mendacious and evil arguments sound intellectual. I think he’s got to be the closest thing to a real Ellsworth Toohey that exists in our world.

We really need instantaneous vote-by-text mobocracy.

We might as well; just go ahead and give to ’em, good and hard, as Mencken suggested.

That actually might be an improvement, if you can design it so that the issue stands on its own without attaching it to a group or political party. I don’t see that happening, though. For most people, asking “Should we do x or y?” will prompt “who’s in favor of x and who’s in favor of y?”

Where’s my Political Tinder App? I’ll swipe right on that.

That would turn into a rapey version of Grindr… immediately.

STEVE SMITH MORE FAN OF RAPR.

Your life is dictated by the people who can’t decide whether to buy beer based up whether it tastes great or is less filling.

Ummm…those girls were hot. I would have no problem with them dictating my life

You mean tick taking, right?

I’m not clever enough to get this. I’m just talking about those girls who use to wrestle in those commercials

Imma guess that was ‘dick taking’?

Hey, we’ve at least progressed to fighting over hoppy beers and malty beers. Progress!

It really is.

Burp.

Yusef really liked your Article Trsh,

/The More You Know

I hate identity politics, but at least it makes sense. We are pack animals (which is why we turned wolves into pets). So we vote to give our pack every advantage we can get over other packs.

#4 even makes sense.

“I dont like either party or dont understand them, so if things are going good, I will keep the party in power and if going bad, will switch it up.”

Option 4a) always vote against the incumbent.

So, you have seen me mark my judicial ballots then?

“Social Science is Modern Day Astrology”

Alchemy hardest hit.

Good article, so says 4 out of 5 Glibertarians

Who’s the fifth one?

Tulpa is all five, of course.

Good article, paralleled only by your choice of classy avatar. However, you sent me into flashbacks and Stats PTSD. Expect a bill from my therapist.

There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.

Figures lie and liars figure.

I saw some “poll shows” article yesterday which had what seemed to me to be an utterly preposterous result (taken at face value, of course, by whatever idiot wrote the story). I don’t even remember what it was, but my immediate response was, “What the fuck were the alternative responses?”

America would be better off as:

a) a patchwork of cannibalistic warlord fiefdoms

b) a corporatocracy in which everyone worked for an all-powerful corporation and lived in communal housing and shopped in company stores exclusively

c) an agrarian theocracy run by the Jesuits

d) a democratic socialist utopia in which everyone was paid a universal living wage to pursue their fondest dreams

Hey, look, everybody! Americans believe the solution to their problems is democratic socialism!

I’ll take cannibal warlords thanks.

Skip the middle man and go right to the Endgame?

Exactly, why suffer through socialism if we know where it gets us? At least with cannibal warlords I can choose my warlord, or my dinner if I’m armed.

Yes, Minister got there first, of course.

Great job trshmnstr! Well thought out and written. I feel smarter for reading it.

Somewhere in my book list it “Pre suasion” by Cialdini. I see he’s mentioned in some of the linked articles. That guy really gets it. I suggest reading anything by him.

Great article, Trashy.

Also don’t forget that there are people, like me, who absolutely refuse to participate in polls. As much to be cantankerous as to be able to point out that polling results are inherently flawed because of people like me. I don’t think it’s possible to measure the number of poll-refusers.

And then there are people like me, that base their answers to polls on figuring out what combination of answers is the funniest while still being plausible.

Ohhh, culture jamming. I approve.

They always seem to get confused when I say I’d vote for neither of the candidates they’re asking about.

I say I’m voting for both.

Why won’t you conform to the binary choices determined for you by your betters? Don’t you realize that you really only have two choices.

I think I had about 5 or 6 calls where they asked that binary question.

Was kind of entertaining the lengths to which they would go to try and get you to say A or B.

You’re like my housemate in San Diego who would invite the Mormons in for a theological debate.

One of my proudest achievements in irl trolling was starting a theological debate between the door to door Mormons and the door to door Jehovah’s Witnesses while I egged them on by playing a literal devil’s advocate.

The mormons won. No question.

“My Daddy raised me chaotic neutral, and I ain’t gonna change!”

Chaotic Neutral – I like to keep my options open.

Two very attractive door-to-door Mormons came to my house. I let them talk. I didn’t listen to a word they said and I think I might have drooled. After about a minute or so they wanted to come in and I said “I wasn’t prepared for a 3-way but OK.” And they went away in a huff. Goddamned bait-and-switchers.

The last political poll I took over the phone, I indicated that I was a National Socialist. The poller didn’t even hiccup.

You guys…

Anti-narrative:

http://getschooled.blog.myajc.com/2018/01/16/betsy-devos-common-core-is-dead-at-u-s-department-of-education/

Wow, that’s something. I don’t know if it’s on purpose, but this type if real change is happening while everyone is distracted by conversations about shitholes.

If this type of education reform were the only thing Trump accomplished, I’d still call him a success.

I think its funny that the left was absolutely opposed to the centralization of education-standards under the Bush admin, but political opposition effectively stopped as soon as Obama took office, and the same policy was basically continued.

now DeVos is essentially coming back to that early 2000s view that the Federal govt shouldn’t get be in the business of setting standards or guiding curricula – something the teachers unions argued for many years.

Now they will turn on a dime and now demand that Devos keep these standards, because they had invested so many resources into learning how to game them and use them as a means of guaranteeing federal funding. I’m not 100% how obama modified the common core stuff, but i presume that was the purpose – to give schools a toolbox/checklist to help secure more sugar-daddy money.

I’m not much of a reader or a writer, so I have no idea how fucked up common core is there.

I made it clear to my kid’s 4th grade teacher that he would not be learning math that way, though. I actually got a decent reaction out of her.

Common Core is everything you would expect of an educational program designed by committee.

I got around that by making sure my kids were able to read and do basic math by the time they got to kindergarten. It was funny, because after a while my son started counting the abacus beads in his head.

I read the common core standard for math. They are just a list of expectations for comprehension of concepts at different grade letters. They expectations were a bit aggressive, but not outrageous.

The issue with “common core” is the industry that sprang up to create teaching and testing materials that were both totally useless for teaching math concepts and totally overrun with progressive ideals.

Testing materials especially. Standardized testing is a huge industry, dominated by a few politically connected players. And the teachers spend a lot of time prepping students for these tests.

I had a big problem with the “estimate” portion.

My kid is in 4th grade. He’s going to give you the correct answer, not an estimate.

They spent the 1st three weeks learning how to estimate. Sorry, not happening.

I remember the first time one of my kids brought home a common core math assignment. It was a simple subtraction problem, but they wanted them to go through a bunch of steps to get to an even number or something. I said, fuck that, just subtract one number from the other. Tell your teacher to talk to me if she has a problem with it.

I have a handful of friends in public education (in nyc mostly). they say its bad in its approach to english and history, but math is particularly bad, apparently.

i personally think the idea of trying to apply any kinds of standards to age groups below junior-high (6th grade and up) is insane, and ignores basic facts about child-cognitive-development which occurs at wildly different rates in ages 4-11. there is literally no such thing as a “3rd-4th grade reading level” because some kids still don’t read (and its not because they’re ‘dumb’), and some are reading stuff many years above their ‘age’. development is not linear and its not evenly distributed.

Because those that teach teachers don’t actually understand fucking mathematics.

http://www.news-gazette.com/news/local/2017-10-26/ui-defends-professor-after-book-chapter-draws-attention.html

Plus, you know it wouldn’t matter anyway what the actual result would be. Teachers’ unions have too much invested in DeVos as Satan, to not oppose whatever she announces. I’m sure we’ll hear shrieking about this from the usual DNC mouthpieces shortly.

“CHILD MURDERING BETSY DEVOS TODAY DECIDED TO DESTROY EDUCATION FOR ALL CHILDREN!!!”

Yeah, and I’ll bet we see liberal (no pun intended) use of the sunk-costs fallacy out of ’em.

This is excellent and a topic that drives me crazy on a regular basis.

One of the first things i learned to do ‘on the job’ was “how to read *through* numbers”:

i.e.

– ‘how were these #s defined (what is the unit and is it appropriate)?

(e.g. ‘gun deaths’ used to make claims about crime-reduction policy….when 60%+ are suicides, and irrelevant to the question)

– are changes in the numbers part of a secular trend (steady over a long period), or simply normal deviation?

(e.g. see claims of a “war on cops” because of a sharp rise in cop-deaths over 2 years …within a 40+ year period of steadily declining cop deaths due to violence)

– are changes in the number organic, or artificial?

(e.g. are ‘15% higher revenues’ for x retail company due to higher same-store-sales? or a reflection of 30% expansion of their total retail footprint? how do higher-prices, inflation, one-time recognition of income from divestments, etc. influence that #?)

..and on and on and on. never mind ‘polling’; 90% of journalists seem completely incapable of looking at any set of numbers and actually seeing anything but “bigger number means more better”. You actually find people who still *don’t understand* why Liz Warren’s “The metric is money!” makes no fucking sense at all.

Its not about ‘math’ or even statistics – there’s some very basic inability to apply common-sense scrutiny to anything involving ‘numbers’.

One the reasons word problems are so difficult for most students is that they are taught from the beginning that math is a set of rules governing abstract symbols instead of a way of understanding the real world.

It’s like trying to teach people English by copying words out of the dictionary.

If children were forced to learn English the way math is taught, there would be a lot of grunting and pointing.

Look up “Sight words” some time. It’s a guaranteed way of teaching functional illiteracy.

But that’s how the Chinese learn!! And they’re taking over!!!

The main factors the fuelled chinese expansion are largely exausted at this point. All of the previous 7% years were the easy gains. It has had the unfortunate (for China) effect of ingraining bad habits that will hamstring the transition to the next stage of development.

Also, I heard somewhere that a lot of the international educational attainment comparisons are tainted by the fact that a lot of countries only report from their top eschelon students and the US, being chumps, reports the whole cohort. I do not know the accuracy of this claim.

Also, I heard somewhere that a lot of the international educational attainment comparisons are tainted by the fact that a lot of countries only report from their top eschelon students and the US, being chumps, reports the whole cohort. I do not know the accuracy of this claim.

This is a problem in general with comparing statistics between the U.S. and other countries. The U.S. is, for better or worse, more egalitarian in its statistical reporting. It is very rare that an apples-to-apples comparison can be made between the U.S. and other countries using headline numbers. You typically have to adjust our numbers or theirs before the comparison can reasonably be called representative, and that still assumes methodological consistency on both sides. Sometimes this is intentional, to game the numbers, and other times it is just a consequence of different policies. For example, many countries start weeding people out of the academic track of their educational systems well before college, and/or filter students into different high schools based upon test scores or other criteria, whereas the U.S. requires high school to be open to everyone and most people go to their local high school regardless of interests or ability.

Also, the outright test fraud.

this same point could probably be applied to statistics regarding ‘public health system efficacy’

the US spends whopping amounts keeping unhealthy people alive who would otherwise simply die of ‘natural causes’ in some other systems. the idea that other countries ‘free healthcare’ is somehow better on an apples-to-apples basis is near impossible to claim.

Speaking of public health system efficacy:

http://www.businessinsider.com/hemophiliac-iowa-teenager-costs-12-million-a-year-insurance-obamacare-2017-6

“Success story”

There is also lots of ‘false quantification’. Think about grading an essay. Even when you have a rubric, is there really that much difference between a 95 and a 97? Is the difference the same as the difference between a 75 and a 77? People will act as if that’s true, and the difference is the same.

My favorite econ joke: how do you know economists have a sense of humor? They use decimal places.

Two quotes stolen from Derpetologist (that I absolutely love and have used several times by now):

“If you torture data enough, you’ll get it to confess what you want.”

“Statistics are like bikinis; what they reveal is suggestive, what they conceal is vital.”

It’s OK. I stole them as well.

You forgot my favorite:

Every 2 hours in New York, a man is hit by a car. He must be getting tired of that.

Here’s another good one:

Understanding that a tomato is a fruit? That’s data.

Understanding not to put a tomato in a fruit salad? That’s knowledge.

Paging SP. I just refreshed this page on a W7 PC running Firefox and the color scheme just changed. I’m indifferent to color choices but the text is now gray and hard to read.

/old guy rant

And now it’s back the way it was.

Stop crying wolf!

Yeah, *someone* is re-theming the site in realtime.

Grays, solid buttons with rounded corners, harder on my old, failing eyes ….

Just take some Citrucel, that will make it better.

/old guy advice

As a final note, 35% of respondents randomly varied across opposing positions for issues in successive interviews. There wasn’t a trend in these changes, which made the pollster come to the conclusion that these people weren’t able to come to the same opinion two interviews in a row.

I find this completely unsurprising. Amusing, nonetheless.

“Question Order Bias (“Priming the Pump”)”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5xC2bNpXdAo

Surveys are crap.

Just ask millennials.

LIBERTARIAN MOMENT!

This is the Nick Gillespie of ‘Libertarian Moments’

Ask? I thought we were supposed to pole them?

*Puts halberd away*

Pole them?

*unzips pants”

I agree, but let’s have a poll so we can find out what everyone else thinks.

trshmnstr,

I’m curious as to your opinion of using computers/text to speech systems to smooth out some of those biases. And not in the sense of online polls which are they’re own very special kind of flawed.

Lipstick on a pig, IMO. I think the telephone problem is intractable, so public opinion polling is fundamentally flawed until we’re each issued our citizen’s response pad upon birth. I don’t think it means that the polls are meaningless, but I think that the error in the polls are much higher than stated.

This is really well done, trshmnstr. I will second the nod for How to Lie With Statistics which as a former VA employee, I may or may not have read.

Apparently, I may or may not know how to use tags either.

Journalists are morons, exhibit 42A

http://www.foxnews.com/entertainment/2018/01/18/joy-reid-backtracks-comments-on-conservative-david-french-after-bipartisan-twitter-beat-down.html

***

MSNBC star Joy Reid was forced to backtrack racially charged comments on a conservative commentary after they were mocked on Twitter by users across the political spectrum.

It all started when Reid responded to a piece written by David French that theorized a hypothetical nuclear attack on the heels of the false alarm that occurred in Hawaii last weekend. The conservative French noted that a “strike would devastate central Honolulu but leave many suburbs intact.”

Reid failed to read French’s actual story that was published in the National Review, instead opting for watered-down, misleading pickups that were published by Newsweek and Raw Story that focused on Trump supporters living in rural areas. The MSNBC host then twisted the already watered-down versions of the story to make it about race.

“We have truly entered the age of insanity when the conservative argument in favor of risking nuclear war is, ‘don’t worry, it will only kill Democrats and minorities.’ Shame on you @DavidAFrench,’” Reid wrote.

Reid was immediately mocked across Twitter for her take. French responded himself, calling Reid’s tweet “misleading and ridiculous.”

***

I watched about 15 minutes of MSNBC the other day before I reached the limit of my derp endurance.

But are they? I suppose you could call them morons if they were held accountable for their outrageous pronouncements and they continued to do it.

Hmm. Clumsy shill then.

I miss the good old days, when the patriarchy gave us Chet Huntley and David Brinkley instead of young twats with a twitter account.

Excellent article. Well done.

OT: The mask slips off revealing that modern feminism always was about power and vengeance.

https://www.thecut.com/2018/01/maybe-men-will-be-scared-for-a-while.html

I’m not scared. I’ve never sexually harassed anyone, and I’m good at my job.

Maybe women will enjoy being avoided by men for the rest of their lives

I was thinking of putting together a hugeass Excel spreadsheet of names of women who have screamed ‘rape’ at any time in their lives, so sane men can avoid them like the plague,

There (should be) an app for that.

Unlike that spreadsheet that hit the fan a month ago, it’d be easy to avoid being slandered. You could just set up the app on your phone, put in a name (have to figure a way to discriminate between women with the same name, or maybe that isn’t important), and just have a couple of check boxes. Data is posted anonymously.

Name Has claimed abuse by a man

Elizabeth Nolan-Brown [ ]

She’s not being accused of being a criminal or a bad person. It’s an anecdotal observation about how she behaved in the past. She might not even remember saying she was abused, she can’t be expected to remember everything she’s ever said. It’s just a piece of advice to anyone who might want to get withing hailing distance of her and ask for a sammich.

Definitely not important

Oh, and then reward people who post consistently and heavily with little blue icons “Hero Snitch” or something like that. I reckon pretty soon we’ll collect warnings about every woman who should be profiled. Just need to build a back-end app that can capture the names of about 150 million people.

Once you had enough data, it’d be pretty easy to do a predictive analysis on the percentage chance that:

1) You’d have a shot at getting laid

2) If you’d be accused ex post facto

I think we have a winner here.

“(have to figure a way to discriminate between women with the same name, or maybe that isn’t important)”

Close enough for the no-fly list.

Rapebook

Nice, except it might be barred from the App Store with a name like that.

Maybe something provocative, like “Cry Wolf”.

With a slogan like “Because sometimes, there is a wolf”.

Thinking about it, make TWO apps. Call the other one #MeToo, and women can download that and enter their own details. The data goes in the same database.

BRILLIANT!

Because sometimes, there is a wolf

Sometimes there’s a wolf (or maybe just the wolf’s head) that has experience with full stack development. I’ll help make this just for shits and giggles. The database will take a bit of time and I only have barebones experience with machine learning, but I can knock out a working prototype app in a day or so.

All it needs is a Key-Value database on the back end.

The app has a search that just lets you type in “Nolan-Brown, Elizabeth” and it tells you whether anyone claims to have ever heard her complain about men.

If we can monetize this, I’m going to open a chain of kitten-farms that also sell vibrators and sybians to sell to all the lonely, bored and sexually frustrated women.

I’ll mock something up. I was looking for a nonsense project to keep my skills sharp. I also wanted to try using Scala for Android development, and this is funny enough to keep me interested.

Help! instead of Yelp?

How about this.

Build an app called “Help! MeToo!” that women can download and submit their name and a few binary checkboxes on what they say has happened. PIV Rape, CatCalling,”Felt Uncomfortable” etc. You can discriminate between duplicate postings (which you let them do) because you have an ID for the app, because of the app store user ID. The submissions are flagged as ‘first person reports’. You ensure there’s no way to allow them to provide detailed information.

This is a “SOLIDARITY, SISTERS!” moment for teh womyn. You leave them at it for a few months,

You then release the plugin, that reports how many women, by general geographic location, have been victims, because that shows where the rapiest places are, right?

Then you release the other app. The one where third parties can enter their submissions, flagged as third party data. That’s just “she accused me of sexual improprieties” “she claimed I got her pregnant” – all clearly anecdotal.

Then you sit back in your Bond Villain lair, enjoying the sight of your FLBP Bikini’ed bodyguards. And you larf.

I foresee some interesting replacements for stars for person rating (butt holes for crass remarks, wolf icons for cat calls, mattresses for next day regret, etc)

What, realistically, could be wrong with aggregating these MeToo claims? Especially with the claimant submitting the data?

In Europe, they might realize what was happening, and demand to be ‘forgotten’, but other than that?

I guess they could demand the data be redacted or anonymized because they lied, but who would lie about that kind of thing?

Keep it up and I’ll need you to submit a formal requirement document.

Wouldn’t be the stupidest proposal I’ve had to write ….

laughs while nodding head in agreement before slowly devolving into quiet sobbing

Fakebook

this was a pleasure to read

http://www.foxnews.com/opinion/2018/01/17/john-stossel-southern-poverty-law-center-is-money-grabbing-slander-machine.html

John Stossel: The Southern Poverty Law Center is a money-grabbing slander machine

He just gives no fucks what anyone thinks anymore. Love me some Stossel!

Speaking of which, this has the Trifecta: OMG Russians!, Trump! and the evil NRA! FBI investigating whether Russian money went to NRA to help Trump

I think I’ll go buy a Russian firearm to celebrate.

“The extent to which the FBI has evidence of money flowing from Torshin to the NRA, or of the NRA’s participation in the transfer of funds, could not be learned.”

(insert sad trombone)

How is this news? It is nothing more than libel

Libel/slander laws don’t apply to people right of Lenin. Did you miss that in the fine print of the statute?

“Tribune Washington Bureau”

Whatever that is.

If you have a Russian last name, you have close ties to the Kremlin.

I’ve never heard of it either.

Here you go.

https://www.politico.com/blogs/onmedia/0311/A_new_day_at_Tribunes_DC_bureau.html

Hmmm…. suspicious.

“The Greek word for “return” is nostos. Algos means “suffering.” So nostalgia is the suffering caused by an unappeased yearning to return.”

-Milan Kundera

“It is an illusion that youth is happy, an illusion of those who have lost it; but the young know they are wretched for they are full of the truthless ideal which have been instilled into them, and each time they come in contact with the real, they are bruised and wounded.”

-Somerset Maugham

“Every act of rebellion expresses a nostalgia for innocence and an appeal to the essence of being.”

-Albert Camus

“We are dead to love and honor/We are lost to hope and truth/We are dropping down the ladder rung by rung/And the measure of our horror is the measure of our youth/God help us for we knew the worst too young!”

-Rudyard Kipling

For some reason, all this #metoo, awkward sexual detritus, wreckage of human desire clashing with ancient impulse and existential crisis; all wrapped up and nicely tied up with a bow of, as Tom Wolfe would put it, rut, rut, rut, rut…, has got me feeling nostalgia for the heady, hormone flooded fruit of youth.

It was miserable, glorious, intoxicating, heart-breaking and unfathomable. The sense of standing right at the edge of some great unveiling of Truth, of infinite possibility, of *invincibility*; nothing can compare. Senescence, decay, entropy and atrophy are nowhere to be found. It’s a shame.

Death is a constant companion whether you know it or not. You can’t go home again.

I don’t want to go home, I just want to not hurt and be able to perform pirouettes on my penis again.

Drugs man. Drugs.

I know exactly how you feel, just like youth, except the added frisson from the threat of rape charges being brought against you, which if nothing more, will make you feel at least somewhat vincible.

One of the most common (and pointlessly misery-inducing) exercises I catch myself engaging in is how I would do things differently if I were back there with the knowledge I have now. These exercises almost always revolve around getting more pussy, but sometimes are more substantial.

I suspect everyone does this.

True wisdom lies in tagging it as a pleasant fantasy about 0.00005 ms into the idea.

True heroism is taking your son to one side and helping him realize not make the same mistakes.

“Son, that skank you might think better of banging; don’t. You’ll regret not doing it later.”

People always have regrets about things they should have done. Son, here’s a photo album of regrets… 😀

She’s hot, AND a linguist?

One of the most beautiful, alluring women I’ve ever met in my life was a translator at the UN, fluent in eight languages (her native French, English, German, Italian, Spanish, Russian, Polish, Swedish) and spoke a bit of a few more obscure ones like Gaelic and Basque. The girl just had a gift.

She’s a cunning linguist.

I saved a bunch of money this week by not eating.

I think I’m on to something.

Call Geico

One weird trick?

I am too lazy right now to read the article or peruse the comments.

What about us critters that dont follow the crowd? I had a boss once who said in a meeting “Or take Suthenboy there. I’ll give him this, he has balls. If he gets an order that’s out of line he will tell you to go pound sand right now.” A day later I almost lost my job because I told him to go pound sand. I am just not a go-along kind of guy.

I know what y’all are thinking. You are right. I am an asshole. Not oppositional disorder but could probably be misinterpreted as one.

Assholes often get shit done.

/Raises hand in Solidarity!

As Jordan Peterson might say:

I had to take a guy to court in New Orleans, a minor. Our regular van was in the shop so they gave me a rental. Court didn’t go well for the poor guy which is sad because he was incarcerated for something he didn’t do. On the way back he tried to commit suicide by jumping out of the van on I-10. The rental van had no child locks on the doors. WTF man? Ever try to restrain someone and drive 70 mph at the same time? Fortunately I was successful, dont ask me how.

A week later they ordered me to take him again, same van, same court, no restraints. I said no.

“You’ll do it or give your keys up and go home.”

“Ok, here’s my keys”

Half way to my car in the parking lot Chief chases me down. We talked it out. They sent someone else. A year later and identical situation occurred where a guy jumped out of the van and was run over by a tractor trailer rig on I-10.

I have to add this was not the Chief’s decision. He had already made his position clear and he was solid. Word came down from Baton Rouge demanding that cluster fuck.

If any of you assholes try to make anything out of this I am just gonna say the whole thing is a big fat lie. Besides, it’s just a hypothetical example.

https://twitter.com/RepThomasMassie/status/953717967237369856

The comments to Massie’s tweet here shows just how statist the Left has become. They are defending Clapper, because he’s said mean things about Trump. When your paranoid fantasies about ‘literally Hitler’ leads you to defend ‘literally a criminal’, you’ve ‘literally’ lost your mind.

They don’t realize that is exactly how the real Hitler came to power.

That is a little disappointing. Even Massie doesnt get it.

“The integrity of our federal government is at stake ”

No, it’s not. It’s been shit on, shot, hit with a shovel and set on fire. Credibility and integrity are for individuals in any case and I can count the fed officials I trust on the fingers on one hand.

I only skimmed the article but I think the takeaway is that I will give Emily Eakins whatever answer she wants.

Let’s get some research on how to reproduce this for everyone.

http://www.sciencealert.com/common-characteristics-among-people-short-sleeping-disorder

I have about half of those traits, the key one being that I ‘do’ about 4 hours a night, and have done since the early 2000’s. The only apparent problem I have is that I have put on weight and I ………………………

Ketogenic diet plus Clenbuterol for the weight, Modafinil for wakefulness.

As stated: drugs man. Drugs.

I’m somewhat keto. Up at 6AM, no food until noon. Hight protein, very very low carb at lunch. Portion size is the problem.

Down 12 “real” pounds since New Year, about to start testing Y-HCl to see if it cuts the munchies in the evenings.

I’m pretty good about not snacking, but I’ll usually have 12oz of casein at 10PM to quell the hunger.

First processed carbs of the day. 4 saltine crackers. I feel so dirty.

Buy the sticks. They’re a good motivator.

Where do you buy your horse steroids?

Now why would you ever insinuate that *I* buy these things? As discussed with 6 on another thread, a hypothetical friend of mine might consider buy such a compound from a peptide research lab. Sold this way it’s explicitly not for human consumption, so this hypothetical friend would only be using it to perform experiments on her lab rats.

I didn’t know that they sold Clen as a research peptide.

I think big. I’ve been considering a project with lab capybara.

Every post from Q has an undercurrent of reproduction.

https://labs.psych.ucsb.edu/roney/james/other%20pdf%20readings/Thornhill%2520Gangestad%2520Human%2520female%2520orgasm%2520and%2520asymmetry.pdf

Maybe I’ll repost this in afternoon lynx because it’s an example of how ruthless biology is.

Female orgasm (strictly from PiV) is correlated with male genetic superiority as measured by facial symmetry *independent of relationship quality*. Meaning, no matter how much she loves a guy, if he can’t make her cum, he is genetically inferior.

I fucking hate that Trivago guy.

Didn’t HM have a post about that way back when?

Why? He’s just an actor.

The Trivago guy is the Arthur Fonzarelli of Nick Gillespies or something

I can’t Stand the Disheveled “look”, intentionally Grey hair?

That Guy’s a fag

And his shit’s all retarded.

Yep, the essence of it that Nth Am got stuck with a middle-aged white guy as spokesman whereas other countries had hip dudes, hot chicks, etc. UK went a little but further (possibly moderately NSFW): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qkmJRhP8KNs

According to Bankrate survey, only 39% of Americans say they could cover a $1000 emergency expense.

My friend, who is a dentist, posted that this morning (along with a reminder that dental insurance is a scam, and to pay him directly).

Its not a scam if it is being subsidized by your employer.

TINSTAAFL

You got a problem with the word Aint?

And yeah, I would probably prefer them pay me more, but that wasn’t an option on the table.

It still can be, depending on the plan.

A government-endorsed scam is still a scam.

Does “Eligible for loans at CashFirst America” count as being able to cover it?

I suspect that the number is actually lower.

Probably, I have that much in cash stashed away in my…..

…G-string?

Totally not hysterical

Already the president’s defenders lurch from one argument or another in transparent bad faith. No one is offended by the president’s use of profanity; it is the substance of his remarks, and not the specific word he employed, that is appalling. It makes the president’s remarks no less racist to say that many who voted for him share the same sentiments; it merely means that those voters subscribe to the same racism. The president was not making an assessment of the relative quality of life in Haiti or Norway, he was condemning entire populations of people of as undesirable because of where they were born. Trump’s remarks do not merely express contempt for foreigners; but also for every American who shares their origins.

He should take that mind reading act on the road.

What utter bullshit. I’m willing to bet twenty to one that Trump and most of his supporters would be happy to roll out the welcome wagon to a doctor or physicist from Haiti. And they’d be reluctant to admit a Norwegian derelict or welfare case. They simply don’t want to bring poor people in to the U.S. And, as a matter of policy, they’re probably right. Poor people bring problems with them. And, yes, someone coming to the U.S. from Haiti is going to be more likely to bring problems with them than someone from Norway, on average, because they’re more likely to be poor.

Many countries require you to pay a shitload to become a citizen or at least prove you’ve got fat stacks in the bank as part of the visa process.

Of all of the overreactions, I think this one is going to be the most damaging to the media.

Are they seriously trying to argue that Haiti ISN’T a shithole? Fine. Put your money where your mouth is. Take your next 3 vacations there.

but also for every American who shares their origins

Bullshit. Italy was a shithole when my great-grandparents came here. It’s why they came. I feel absolutely no contempt from someone pointing this out. The broader question, of whether a country’s shithole status should relate to our immigration policy, is what this is ultimately about. But if you want to engage that question then you should try to engage what was said (allegedly) rather than the gigantic strawman you’ve constructed.

Same here. I’ve looked at pictures of the town my ancestors left, Bedonia. It’s beautiful countryside, which made me realize just how shitty life must have been for them there, with virtually no opportunities to improve their lot in life, to make them want to leave that beautiful countryside for the squalor of a pre-WWI Manhattan tenement.

Already the president’s defenders lurch from one argument or another in transparent bad faith.

It’s always projection with the left.

Did Newsweek win a fake news award?

http://www.newsweek.com/hillary-clinton-president-trump-russia-probe-lawrence-lessig-784081?utm_campaign=NewsweekTwitter&utm_source=Twitter&utm_medium=Social

A Harvard Law School professor said that Hillary Clinton could still become president. He is from Harvard; he must be right.

Lessig is a twat. He’s just riding the anti-Trump wave for everything its worth.

They simply don’t want to bring poor people in to the U.S. And, as a matter of policy, they’re probably right.

I remember reading some stories about Canadian immigration policy, at the time of Hong Kong’s lease expiration. The Canadian government policy specifically allowed wealthy Hong Kong Chinese to “buy” their way to the head of the line with proof of wealth and ability to invest in their new Canadian lives. What a novel concept.

I’m cool with poor people as long as they’re not 1) committing crimes and 2) suckling on the government teat. If there were any effort to permanently deport criminal immigrants and restrict immigrants from welfare access, I’d be hopping on the open borders bandwagon.

“restrict immigrants from welfare access”

Technically there is: unless the law’s changed, immigrants are not eligible for welfare for at least 3 years.

Is that all assistance or just certain programs?

Just certain programs, but most have a work-around and significant state discretion.

Yeah, I should have clarified: the prohibition is on federal programs.

I was already here and working but still had to have a sponsor who would make sure I did not end up on welfare for the first three years.

Children born here are U.S. citizens at birth, and thus state programs (which may be federally funded) that assess eligibility for benefits by the child’s status rather than the parents’ don’t fall under this rule.

I think the disconnect between open borders libertarians and “less open” borders libertarians is that the former look at the issue entirely or primarily as an individual rights question while the latter look at it primarily as a foreign policy question. I don’t see any easy way to bridge that gap intellectually, and thus the only possible solution as long as both factions exist is a political compromise that will be impure to the idealists and too lenient for the pragmatists.

I’ve tried barking down the individual rights path, but I consistently run into the issue of property rights as a styling block to open borders. There seems to be some right to transit built into some people’s worldviews.

Stopping*

Disclaimer: I lean more open borders than not

I don’t see a property rights violation in the general case of immigration. There is no special exception allowing immigrants to trespass or steal from private citizens and the public spaces like roads and parks are, well, public*. That leaves to me the question of government property and government services. I think both should be curtailed drastically, and if that can happen, then I don’t much care about the immigrant-vs-citizen question (if we reduce government by 90% then an extra 5% of what remains doesn’t phase me one jot). But I will grant that most of these ideas are premised on things which currently don’t hold, and thus are more idealistic than pragmatic.

* = Obviously public spaces like roads and parks have to be maintained, and that maintenance is paid for by taxpayers. But I think the government is only entitled to own property for certain purposes, namely statehouses, courthouses, and military bases (I’ll grant post offices as well but I’d strike the postal authority from the Constitution if it was up to me), and that if it holds other property it does so in trust for the public benefit. The exercise of a right of ownership, like exclusion without cause, against some member of the public to my mind contradicts that purpose. So that leaves two solutions, one is to accept that public spaces will be used by non-citizens and the other is to sell the property into private hands which can exercise exclusivity.

While not called a right of transit, common law does provide right of way, right of roam, and right of access exceptions to private property. Historically, it isn’t an anomaly to have an exception to trespass to allow people to move over private property for some lawful purpose provided they do so in a non-destructive way as efficiently as possible.

You may or may not agree, but there are a few centuries of precedent and jurisprudence backing that idea up.

IIRC, such lawful trespass was for emergency use only. Perhaps there would need to be a rethink if there were no longer public land, but I think that asking and receiving permission for transit would be part of non-emergency transit.

No, those rights I mentioned are for non emergency, general purpose use. Especially the right to roam, which is specifically for recreation and can establish a permanent public access to private land in the UK (specifics differ in England, Wales, and Scotland on how such easements are developed). I’m no lawyer, and I’m certainly not an expert on common law and how it’s changed over the centuries in different countries, but the idea that the public could access private land was a common one, no pun intended, at one time. It’s less used now, and I suspect it probably came into being due to the large amount of land held by the crown, and therefore may not be applicable to modern rights frameworks, but the justifications are around if you’re interested.

To clarify, I’m not offering a different view on a right of transit, just pointing out that a differing view exists with a long history behind it if you’re interested in looking into it.

Poor people are fine, they’re great even. The problem arises when there is no political stomach for acceptance of the risk inherent with the move. Poor people may not be able to get jobs, this in no way obligates the host country to make it better.

I’m cool with poor people as long as they’re not 1) committing crimes and 2) suckling on the government teat.

Absolutely. There have been thousands (if not millions) of immigrants who washed ashore in this country with little more than the shirts on their backs and gone on to build successful and rewarding lives.

I just wonder sometimes about the weird attitude which requires being willfully blind to the resources and circumstances of people who want to come to this country. And- as I have said many many times in the past, I don’t see why residence demands citizenship.

I don’t see why residence demands citizenship.

Amen! If Trump wanted to fix DACA and fuck the dems at the same time, he’d give the “dreamers” permanent residence with no path to citizenship in exchange for wall funding.

I think that is still problematic with anchor babies. Remove automatic citizenship for being born on American Soil, eliminate any sort of welfare for non-citizens, and then I think you would see much of the resistance fold.

Remove automatic citizenship for being born on American Soil

The fundamental problem with this is that citizenship now becomes something declared by a bureaucrat. This will cause way more problems than it will solve.

A birth certificate as evidence of citizenship is a nice clean test.

I don’t think that would be the case since having an American citizen as a parent would still confer automatic citizenship. The immigrants entering legally are already neck deep in the bureaucracy. The immigrants entering illegally are the only people who would be affected.

The problem is the perks that come with citizenship, not the citizenship itself. Sorry, anchor baby can stay, but illegal mommy and daddy have to go. Take your kid with you or make arrangements for them to stay.

I have a problem with conferring citizenship if the illegal population trends towards supporting socialist policies.

Give me your poor, tired, and hungry fleeing from ex-Soviet bloc countries that appreciate liberty and freedom.

While I don’t have a problem with that solution, the concept of “permanent residence with no path to citizenship” is only guaranteed to last until the next congressional election.

My old man had a pretty good solution to this one, put it back on the parents. Parents leave the country, go back to wherever they illegally entered from and the kid can stay. Otherwise, everyone goes.

But a lot of that was when we had a very different economy. In the nineteenth century those people could head for the frontier and homestead. In the early twentieth century people would show up job-ready with useful skills like shoemaker or blacksmith.

But, muh net neutrality! Look how popular it is!

David Frum- still a blithering idiot

Election 2016 looked on paper like the most sweeping Republican victory since the Jazz Age. Yet there was a hollowness to the Trump Republicans’ seeming ascendancy over the federal government and in so many of the states. The Republicans of the 1920s had drawn their strength from the country’s most economically and culturally dynamic places. In 1924, Calvin Coolidge won almost 56 percent of the vote in cosmopolitan New York State, 65 percent in mighty industrial Pennsylvania, 75 percent in Michigan, the hub of the new automotive economy.

Not so in 2016. Where technologies were invented and where styles were set, where diseases cured and innovations launched, where songs were composed and patents registered—there the GOP was weakest. Donald Trump won vast swathes of the nation’s landmass. Hillary Clinton won the counties that produced 64 percent of the nation’s wealth. Even in Trump states, Clinton won the knowledge centers, places like the Research Triangle of North Carolina.

The Trump presidency only accelerated the divorce of political power from cultural power. Business leaders quit Trump’s advisory boards lest his racist outbursts sully their brands. Companies like Facebook and Microsoft denounced his immigration policies. Popular singers refused invitations to his White House; great athletes boycotted his events. By the summer of 2017, Trump’s approval among those under thirty had dipped to 20 percent.

And this was before Trump’s corruption and collusion scandals begin to bite.

Dumb hicks in flyover country, too stupid to vote for Hillary, are wrecking America.

People may be rejecting the Trump brand, but they’re also rejecting progressivism.

If you care about “progressive” values, vote republican. We have the lowest black unemployment rate in history right now.

And that pisses the progs off to no end. Also, it’s the result of the policies of the previous guy.

That’s all a holdover effect of Obama’s policies!

/Progtard

Except that those policies have been overturned already, with positive effects.

Frum’s going full elitist, what a surprise.

going?

I can see him waving his wine glass, lower lip hanging ponderously, while he nods in agreement to all the concerns of his 5th Avenue friends.

Intellectual Giants! Titans of Social Media!

I always love this one. Maybe it’s ‘cos I’m even less agreeable than Suthenboy, but if someone I “looked up to” – like Steve Howe – was invited to the White House and he said “fuck dat shit, no – Trump is da debil!”, my only reaction would be a yawn. Even *IF* I thought the inhabitant of the White House automatically deserved respect and obesience, I’m not sure it would bother me much.

Unless you’re so invested in making sure a level 17 hero doesn’t diss a level 19 hero, it’s hard to understand the whole mindset.

Frum only mentions it because he probably grovels at their feet. The man strikes me as needy social climber of the worst sort.

Frum is the cosmo version of conservative…Cosmoservative?

AKA disingenuous ass-clown.

Frum is almost the stereotype of the spineless slave of popular opinion. If no one else remembers, he was the asshole who, after 9/11 responded to Bill Maher’s snark by saying that people needed to watch what they said.

He can come to my house instead. I will provide the beer and he can bring part of his guitar collection.

Or did you mean the dead baseball player?

The former.

I have a distinct feeling though, that Howe isn’t a particularly friendly chap. Maybe someone on here can throw some light on what might be a wicked libel.

While I would hardly disagree that Calvin Coolidge (Silent Cal) and Donald Trump (Twitterer-in-Chief) are two very different Presidents, the people Frum is talking about are even more different. The urban economic engines of the 1920s have been replaced with the dysfunctional and stratified urban areas of today. The lightly regulated economy of 100 years ago has been replaced with a stultified regulatory morass that has resulted in a great deal of economic activity being illegal or so impractical as to be functionally illegal. Government spending was in single digit percentages of GDP in the 1920s; since then, it hasn’t dipped below 15% since just after WW2.

The voting blocs associated with the areas that generate the most wealth today are utterly disconnected from economics in a way that just wasn’t so in the 1920s. It is as though the great government evil of the 1920s, Prohibition, was repealed and replaced with a hundred different little prohibitions whose combined weight far exceeds the original, and yet nobody will own up to it.

Put another way, the U.S. has been on a wartime footing ever since WW2 regardless of actual military engagement because the Top Men of the 1940s (and every decade since) thought it was just swell that so much economic activity got funneled through government. Combine that with a puritanical fetish for banning things, and you arrive at the present day. Modern day “intellectualism” is bankrupt because it stopped engaging with reality and has instead been building on a growing stack of fantasies, aided and abetted by the welfare-warfare state. Trump is an unpolished and uncouth man, but he represents a connection with reality* that the academy and many voters haven’t faced in decades, and for many of them, their entire lives. Maintenance of the pleasant fictions is more important to them than closing the cognitive dissonance.

* = He’s also a liar and a shameless self-promoter, but that doesn’t differentiate him from any other politician

In 1924, Calvin Coolidge won almost 56 percent of the vote in cosmopolitan New York State, 65 percent in mighty industrial Pennsylvania, 75 percent in Michigan, the hub of the new automotive economy.

What a dishonest sack of shit. The “Smart Set” of the 1920s treated Coolidge and Republicans of his day with as much, and maybe more, contempt than is leveled out today. Remember, this was the era of “Babbitt”. I’m not really sure if Frum is just too intellectually shallow to know any better than the garbage he writes or if he actually knows he’s full of shit. At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter, I guess. But, damned if I didn’t wish our intellectual and journalistic classes didn’t have more of Mencken and less of Frum, Brooks, and Krugman.

Indeed, “Silent Cal” was meant to be derogatory. But, Coolidge did win the most populous and industrious states of his day and handily won the popular vote (granted, the opposition was split between the Democrats, representing the South, and the Progressives, representing what would become the Northern left via the Democrats a decade later). There definitely has been a shift in politics since then. But, I don’t think that indicts Trump or the GOP on its own. Voter preferences have changed, and while voters are entitled to their votes, that doesn’t mean they’re beyond criticism.

Minor note/clarification: the Progressives of 1924 got most of their support from the Northwest, whereas the Northeast was solidly Republican at the time. The Democrats would later make inroads into the Northeast as well as take over the role the Progressives had played in the Northwest.

If you read a book like “A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America”, you find that the Northwest, especially the west coast, was settled by a lot of Northeasterners, to the point where the author doesn’t even consider these two areas rivals, The cover map shows that the most “contested” populous area is Northeast Illinois with Philadelphia/Baltimore a close second/third. The political hate in these areas is understandable when looked at from that perspective.

But they all think they’re carrying on with Mencken’s tradition. Just look at how much they criticize the current president!

“Hillary Clinton won the counties that produced 64 percent of the nation’s wealth.”

Trump/GOP just increased taxes in these areas – he actually IS taxing the wealthy instead if just pretending to increase taxes on the wealthy while actually increasing the taxes on the middle class (*cough* Obamacare *cough*)

So those areas can vote bluer if they want, but it won’t make a fucking difference.

“cosmopolitan New York State, 65 percent in mighty industrial Pennsylvania, 75 percent in Michigan, the hub of the new automotive economy.”

And these are flat out lies.

“Comsopolitan New York State” WTF??? NYC is cosmopolitan, the rest of the state has always been yokeltarian.

“Industrial Pennsylvania” WTF? The state was even more agricultural then than it is now.

“Michigan, hub of the new automotive economy”. Actually, Northern Indiana was probably more of an automotive hub than non-metro-Detroit Michigan. The Fort Wayne and South Bend areas (as well as Gary) were larger suppliers to Detroit-area auto manufacturers than the rest of Michigan, in part because there were auto manufacturers in those areas that only later got engulfed by the GM conglomerate.

Did Gillespie just get fired?

https://reason.org/news_release/katherine-mangu-ward-named-editor-in-chief-of-reasons-print-digital-and-video-journalism/

I heard Everyday Feminism is hiring……

Sort of sounds like a demotion to me.

Of course,

*heads off to TSTSNBN to see John’s verbal explosion*

Oh good lord I’m sorry I did that.

How do you emphasize a relationship that would accurately be described as “the two things have nothing to do with each other whatsoever”? It’s like a stupid person tried to come up with a zen koan.

That’s Everyday Feminism level stupid. I hope it’s just a troll.

It’s an Elwick, and a pretty decent one.

But between that quote and earlier discussion of MacArdle piece, I’m reminded of the incomparable Blighter, a true master of the form who caught many, many people back in the day on The Atlantic, Daily Beast and Bloomberg. Sigh…

Blighter was a true master.

Apologies for the naivete, but what is an Elwick?

OK, I’m ignorant on this. Edumacate me.

Peter Suderman as new managing editor of Reason.com,

Will watch to see if the TDS is curtailed some. KMW has kept the actual magazine on a more even keel than what happened at .com.

Sigh…I was hopeful for that very reason, but why Suderman? Shackford or Sullum or even Welch would be better (2Chilli and Stossel would be better yet, but I don’t think they’d want the extra work required).

Maybe it’s like the Chicago Bears coaching job was 12-15 years ago. The 5th person offered it finally accepted the job.

We need 2Chili over here. He was my favorite writer there.

Stossel’s awesome too, but he’s too famous to bother with scum like us.

“Nick Gillespie, dubbed the “intellectual godfather of Reason” by The New York Times, has decided to move to an editor at large position so he can focus his time on content creation. Gillespie, who joined Reason in 1994, will write, host podcasts, create long- and short-form videos, and make public appearances to discuss libertarian ideas and explain the importance of free minds and free markets.”

Becoming a meme at a dissident blog didn’t help either.

I prefer Contrarian

Nick Gillespie, dubbed the “intellectual godfather of Reason” by The New York Times, has decided to move to an editor at large position so he can focus his time on content creation. Gillespie, who joined Reason in 1994, will write, host podcasts, create long- and short-form videos, and make public appearances to discuss libertarian ideas and explain the importance of free minds and free markets

Wow, we really feel the need to correct. I was the only one without ” “

Yeah, I’m embarrassed now.

OTOH: I did find this over there: http://reason.com/blog/2018/01/18/electric-dreams-safe-space-libertarian

Nick Gillespie, dubbed the “intellectual godfather of Reason” by The New York Times, has decided to move to an editor at large position so he can focus his time on content creation. Gillespie, who joined Reason in 1994, will write, host podcasts, create long- and short-form videos, and make public appearances to discuss libertarian ideas and explain the importance of free minds and free markets

he’d give the “dreamers” permanent residence with no path to citizenship

I have no problem with that. None whatsoever.

Sort of sounds like a demotion to me.

They’re just moving him closer to the window in preparation for his inevitable defenestration.

Probably too late for anyone to notice but how are we squaring “Social Science is Modern Day Astrology”, “Manipulating the Results: Bias in the Experiment”, “Manipulating the Results: Playing with the Data” and “The Results are Garbage In the First Place: The Telephone Problem” with “Knowing the Public: What Motivates Voting Behavior?” which is entirely based off of interviews and surveys? Spending an entire article building up how unreliable these sorts of things are makes concluding with definitive statements drawn from research that could easily fall prey to those same errors seems counter-intuitive.

The study at the end was experimental in nature, making it less susceptible to some of the effects as a phone poll. However, I left my undergrad public opinion polling class with largely the same question..

The nature of belief systems:

The American Voter:

I looked up the ANES survey and it still seems susceptible to interviewer and observer effects as well as self selection bias. Haven’t had a chance to check their cross tabs to see if any of the data massaging issues might be there.

At the very least probably not doing the obviously bad things question priming tricks. Although having done political phone surveys, even someone who cares about getting good data will slip and reword their questions as they get more conversational and god forbid the interviewee ask for clarification about a question.